I already stole from CrimeTime.co on Thursday for the Jim Thompson piece, but I wanted to highlight one other great link that I found there: School For Writers: A Prison Cell. It's an article about the many great works of literature written behind bars. An excerpt:

"Writers in prison and prisoners who write have produced, between them, an oeuvre of global significance. From Boethius in 6th-century Rome, they have triumphed over carceral adversity through a combination of willpower and literary excellence. Malory, Bunyan, Cervantes, Vanbrugh and Voltaire might, at first glance, seem a pretty disparate lot. It is only where one throws in their 'previous convictions' that a mutual connectedness becomes apparent. In far-flung prisons across half a millennium, each man managed to transcend his predicament by drawing strength and inspiration from it."

Best of all, this isn't some NPR-produced work of underclass romanticism-cum-condescension. It's written by Peter Wayne, himself a recently released convict/wordsmith.

That's what the kids call 'keepin' it real.'

Friday, August 17, 2007

Bards Behind Bars

Oh No He Didn't!

Via The Associated Press:

Via The Associated Press:

Bill Schneider, Provincetown's administrative director of tourism, has admitted that he made an "error in judgment" by claiming that his self-published book had been selected for Oprah Winfrey's book club and that he had been interviewed by the talk show diva.

(Editor's Note: By an 'error in judgment,' he means 'a motherf**king lie.')

The book, Crossed Paths, was self-published by Schneider in March, and recounts the story of two men who fell in love in the 1970s. One later committed suicide.

(Spoilers: Schneider lives!)

Thursday, August 16, 2007

News Bits...Well, Two Of 'Em, Anyways

Not content with killing the record industry, Apple has unveiled its plans to do the book industry in as well. The first step: Book excerpts are about to be featured on the iPhone.

Not content with killing the record industry, Apple has unveiled its plans to do the book industry in as well. The first step: Book excerpts are about to be featured on the iPhone.

Beowulf comes to the big screen! Directed by Robert Zemeckis, adapted by Neil Gaiman... and starring a CGI Angelina Jolie?

Author Du Jour: Jim Thompson

Biography

(courtesy of: The Killer Beside Me: The Jim Thompson Homepage) Born September 27, 1906, James Meyer Thompson grew up in Oklahoma to become one of the finest pulp novelists of The Cold War era. His life during the Depression and his up and down family history of working the wildcat oil fields of Texas seeped into Jim's dirt-under-the-nails writing as he created characters at displaying both brutality and empathy.

Born September 27, 1906, James Meyer Thompson grew up in Oklahoma to become one of the finest pulp novelists of The Cold War era. His life during the Depression and his up and down family history of working the wildcat oil fields of Texas seeped into Jim's dirt-under-the-nails writing as he created characters at displaying both brutality and empathy.

Thompson began his career as a more "traditional" writer, publishing his first two novels, Now and on Earth and Heed the Thunder as hardbacks. After these books failed to find wide audiences, Thompson found his voice in crime fiction, grinding out hellish tales for paperback mills such as Lion Books and Gold Medal. While on the surface indistinguishable from the rest of their kin, those who dropped a quarter on one of Thompson's novels were exposed to a vision of the world as seen through Thompson's eyes; much of it ugly, little of it good, where redemption goes for a premium and an unnerving honesty to oneself pervades.

Thompson's best known novel is The Killer Inside Me, the story of a doomed small town sheriff unable to control his blood lust as circumstances force him to kill and kill again. Other notable books include Savage Night, The Getaway, and his often-overlooked novella masterpiece, The Criminal.

In the mid-fifties, Thompson began walking the long rough road to Hollywood. He worked with a young Stanley Kubrick on screenplays for two of the director's earliest films, The Killing (w/Sterling Hayden, from the novel Clean Break by Lionel White) and Paths of Glory (w/Kirk Douglas). What would seem a promising start never materialized, and Thompson's screen fortunes took a downward turn after that, and he spent the rest of his career writing unproduced screenplays and teleplays for low-rent television programs like Convoy and MacKenzie's Raiders. Like jazz and Jerry Lewis, Thompson's writings found a life in France. Besides translating several of his novels, two films, Coup du Torchon (based on Pop. 1280) and Serie Noire (A Hell of a Woman), were made to much acclaim by French filmmakers.

Like jazz and Jerry Lewis, Thompson's writings found a life in France. Besides translating several of his novels, two films, Coup du Torchon (based on Pop. 1280) and Serie Noire (A Hell of a Woman), were made to much acclaim by French filmmakers.

A good number of Thompson's works have been put on screen by American filmmakers with varying degrees of success. These include The Getaway (twice, three times if you include the first half of the Rodriguez/Tarantino B-movie rave-up From Dusk 'til Dawn), The Grifters (nominated for four Oscars),and After Dark, My Sweet. The latest, This World, Then the Fireworks (w/ Billy Zane and Gina Gershon), was premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 1997 to a positive audience.

Two biographies of Thompson have been published. The first, Sleep With the Devil, by Michael McCauley, was published in 1991. Savage Art: a Biography of Jim Thompson by Robert Polito, was published by Knopf in 1995. Polito's book won both the Edgar and National Book Critics Circle awards.

Thompson died on April 7, 1977, and had his ashes scattered over the Pacific Ocean. As he had predicted, Thompson did not live to enjoy his own success.

The Classics

(stolen from the highly recommended site, CrimeTime.co.uk)

Nothing More Than Murder (1949)

Thompson's first noir classic and a variation on the old double indemnity shocker. Joe Wilmot and his wife Elisabeth (a woman with "trouble spelled all over her") jointly own and run a profitable smalltown movie house. Their marriage is empty and passionless and made more complicated when Carol Farmer, a business student, comes to lodge with them. Despite Carol's singular unattractiveness compared with Elisabeth, Joe has an affair with her: Elisabeth finds out (she craftily encourages the liaison) and blackmails the couple to fix an insurance scam in which she supposedly dies (substituting an innocent victim in her place) and nets the lucrative pay-off. Murder, arson, blackmail and suicide combine to make an exciting edge-of-the-seat thriller.

The Killer Inside Me (1952) Perhaps Thompson's finest book. Stanley Kubrick called it "the most chilling and believable first person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered." The main character, Lou Ford, a smalltown sheriff, suffers from "the sickness," a psychopathic need to kill. Ford conceals his true identity under the guise of an inept, wise-cracking lawman: in truth he is one smart cookie (he reads psychological treatises and solves calculus problems for enjoyment). He is also a schizophrenic thug with a compulsive need to control, and if necessary, destroy, others. Thompson also invests Ford with a sickening, black humour: "I think I've broken the case," says Ford, after he's just secretly snapped the neck of one of his key witnesses held in custody! This disturbing, compelling masterpiece redefined noir.

Perhaps Thompson's finest book. Stanley Kubrick called it "the most chilling and believable first person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered." The main character, Lou Ford, a smalltown sheriff, suffers from "the sickness," a psychopathic need to kill. Ford conceals his true identity under the guise of an inept, wise-cracking lawman: in truth he is one smart cookie (he reads psychological treatises and solves calculus problems for enjoyment). He is also a schizophrenic thug with a compulsive need to control, and if necessary, destroy, others. Thompson also invests Ford with a sickening, black humour: "I think I've broken the case," says Ford, after he's just secretly snapped the neck of one of his key witnesses held in custody! This disturbing, compelling masterpiece redefined noir.

Savage Night (1953)

A bizarre gangster novel which pays homage to the hard-boiled style of writers like Dashiell Hammett. Savage Night tells the story of Charlie "Little" Bigga, a pint-sized hitman who is blackmailed out of retirement by "The Man" to kill Jake Winroy, whose testimony as a key witness in a racketeering case threatens to expose the mob. Features all the usual Thompson ingredients of human depravity: lust, blackmail, murder, and a particularly gruesome rape scene where the consumptive Bigga ravishes Ruthie, a one-legged girl!

A Swell-Looking Babe (1954) Thompson uses his experience as a former hotel bellboy to supply the authentic background to this novel about Bill "Dusty" Rhodes, a bright, good-looking young nightporter who finds himself embroiled in the seductive Texas underworld. The babe of the title is the vampish blonde bombshell, Marcia Hillis, working a scam with gangster Tug Trowbridge to rob the hotel. Look out for Oedipal images of incest and patricide. A disturbing tale of lust, avarice and murder presented in a third person narrative.

Thompson uses his experience as a former hotel bellboy to supply the authentic background to this novel about Bill "Dusty" Rhodes, a bright, good-looking young nightporter who finds himself embroiled in the seductive Texas underworld. The babe of the title is the vampish blonde bombshell, Marcia Hillis, working a scam with gangster Tug Trowbridge to rob the hotel. Look out for Oedipal images of incest and patricide. A disturbing tale of lust, avarice and murder presented in a third person narrative.

A Hell Of A Woman (1954)

Once again, deadly and alluring femme fatales grip Thompson's febrile imagination. Frank "Dolly" Dillon ("Dolly," incidentally, was Thompson's bellboy nickname while Dillon was his Communist party alias) is a salesman who comes across a depraved old woman who prostitutes her attractive niece (Mona) for downpayments on goods. Frank is attracted to the girl but is still married to his trampish wife, Joyce. Mona discloses to Frank that the old woman has a hidden hoard of cash ($100,000) and together they plan to kill her, setting up an unsuspecting alcoholic hobo to take the fall. Things are complicated by the suspicions of Frank's wife and his creepy boss, Staples. Expect blood, infanticide, pumpkins(!), blackmail, more twists and turns than Spaghetti Junction and the disintegration of the narrator's personality on the final page. Gripping stuff!

After Dark, My Sweet (1955) The compelling tale of an escaped mental patient and ex-boxer (William "Kid" Collins) who gets mixed-up with a crooked ex-cop ("Uncle Bud") and booze-sozzled, spiky femme fatale (Fay Anderson). Together, the threesome hatch a plot to extort ransom money from a wealthy family by kidnapping their son from school. "Kid" Collins, however, is set-up by his treacherous accomplices as the fall guy in this taut, gripping novel of avarice, lust, betrayal and ultimately, sacrificial redemption.

The compelling tale of an escaped mental patient and ex-boxer (William "Kid" Collins) who gets mixed-up with a crooked ex-cop ("Uncle Bud") and booze-sozzled, spiky femme fatale (Fay Anderson). Together, the threesome hatch a plot to extort ransom money from a wealthy family by kidnapping their son from school. "Kid" Collins, however, is set-up by his treacherous accomplices as the fall guy in this taut, gripping novel of avarice, lust, betrayal and ultimately, sacrificial redemption.

Wildtown (1957)

Lou Ford returns but this time as a more humane, benevolent figure (and obviously at a time pre-dating The Killer Inside Me).

The action is set in the seedy location of Ragtown featuring David "Bugs" McKenna as a prickly, paranoid ex-con who accepts a job as a hotel detective. McKenna believes he has been hired to knock off the infirm, wheelchair-bound hotel owner by the man's glamorous young wife. Bugs accidentally kills the embezzling hotel accountant and is then plummeted into a dark world of easy sex, bloody betrayal and multiple double-crosses. Nasty!

The Getaway (1959) What starts off as a simple bank heist yarn eventually mutates into an horrific nightmare when the book's two major protagonists, Doc McCoy and his wife Carol, find sanctuary in the kingdom of the enigmatic dictator, El Ray. After escaping capture by enduring two days in underground caves and being holed up in a mound of farmyard dung, the McCoys find that the mysterious El Ray's kingdom they flee to is no safe haven. In fact, it's hell on earth, where fugitives have to pay for their liberty with added financial and psychological interest. It's a place where one's worst imagined fears become incarnate. The effect of Thompson's grim metaphysical musings at the book's conclusion still divides the critics (both film versions dispensed with the book's original, arguably unfilmable, ending). A disturbing masterpiece.

What starts off as a simple bank heist yarn eventually mutates into an horrific nightmare when the book's two major protagonists, Doc McCoy and his wife Carol, find sanctuary in the kingdom of the enigmatic dictator, El Ray. After escaping capture by enduring two days in underground caves and being holed up in a mound of farmyard dung, the McCoys find that the mysterious El Ray's kingdom they flee to is no safe haven. In fact, it's hell on earth, where fugitives have to pay for their liberty with added financial and psychological interest. It's a place where one's worst imagined fears become incarnate. The effect of Thompson's grim metaphysical musings at the book's conclusion still divides the critics (both film versions dispensed with the book's original, arguably unfilmable, ending). A disturbing masterpiece.

The Grifters (1963)

The classic tale in which Jim Thompson gives the lowdown (with the help of sadistic mobster, Bobo Justus) on how to serve oranges to a person you don't like! Roy Dillon, the son of Lillie, a racetrack collector for the mob, is master of the "short con." He has a romantic entanglement with another expert grifter, Moira Langtry, who sells sexual favours to her landlord in return for the rent money. Together, the three characters get caught up in an incestuous, double-crossing menage-a-trois culminating in betrayal, infamy and murder. Another Thompson masterpiece.

Pop.1280 (1964) Lawman Nick Corey is fat, lazy, foul-mouthed and an irritating practical joker. His memorable, moronic catchphrase is "I wouldn't say you was wrong, but I sure wouldn't say you was right, neither." But like Lou Ford before him, Corey is a sharp-witted malevolent killing-machine masquerading as a witless, innocuous clown. Set at the turn of the last century in a backwater town, Pop.1280 begins as a raucous, almost farcical comedy but descends into an apocalyptic bloodbath. A dark, disturbing novel that ranks alongside Thompson's best work.

Lawman Nick Corey is fat, lazy, foul-mouthed and an irritating practical joker. His memorable, moronic catchphrase is "I wouldn't say you was wrong, but I sure wouldn't say you was right, neither." But like Lou Ford before him, Corey is a sharp-witted malevolent killing-machine masquerading as a witless, innocuous clown. Set at the turn of the last century in a backwater town, Pop.1280 begins as a raucous, almost farcical comedy but descends into an apocalyptic bloodbath. A dark, disturbing novel that ranks alongside Thompson's best work.

The Rest:

Now And On Earth (1942)

Heed The Thunder (1946)

Cropper's Cabin (1952)

Recoil (1953)

The Alcoholics (1953)

Bad Boy (1953)

The Criminal (1953)

The Golden Gizmo (1954)

Roughneck (1954)

The Nothing Man (1954)

The Kill-Off (1957)

The Transgressors (1961)

Texas By The Tail (1965)

South Of Heaven (1967)

Child Of Rage (1972)

King Blood (1973)

The Rip-Off (1987)

Novelisations:

Ironside (1967)

The Undefeated (1969)

Nothing But A Man (1970)

Screenplays:

The Killing (with Stanley Kubrick)

Paths To Glory (with Stanley Kubrick and Calder Willingham)

Posted by

Inkwell Bookstore

at

12:20 AM

![]()

Labels: author profiles, book reviews

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

News Bits, In Brief

Punishing Your Kids -- From the Cradle to the Grave! Newsday.com heaps more fuel on the anti-geek fire by promoting Sci-Fi Baby Names, a book advertising "500 Out-of-this-World Baby Names from Anakin to Zardoz," with explanations as to each one's origin, character, and a trademark quote.

Newsday.com heaps more fuel on the anti-geek fire by promoting Sci-Fi Baby Names, a book advertising "500 Out-of-this-World Baby Names from Anakin to Zardoz," with explanations as to each one's origin, character, and a trademark quote.

Prospective parents of the Comicon crowd, as a fellow cosplay fetishist, I beseech you: Unless you're planning on giving your kid double their required amount of lunch money every day until they graduate, and are then willing to shell out good money for a mail order bride/groom/lovedoll, do not name your children after sci-fi characters. It's not only cruel, it's impractical. Do you know how hard it's going to be to find monogrammed paraphernalia that features the name Zardoz?

Killer Lineup of Upcoming Book Releases According to E! Online, "a literary agent working on behalf of Ron Goldman's family said Monday that she has found a publisher for O.J. Simpson's once scuttled hypothetical memoir, If I Did It, which contains passages describing how the ex-NFL star would have gone about killing Goldman and his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson, if he had been the one

According to E! Online, "a literary agent working on behalf of Ron Goldman's family said Monday that she has found a publisher for O.J. Simpson's once scuttled hypothetical memoir, If I Did It, which contains passages describing how the ex-NFL star would have gone about killing Goldman and his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson, if he had been the one

to commit the double murder." In semi-related-depending-on-how-you-vote news, The Washington Post reports some secondhand information overheard at a hunting lodge: Karl Rove plans to write books after he leaves the White House 18 months from now.

In semi-related-depending-on-how-you-vote news, The Washington Post reports some secondhand information overheard at a hunting lodge: Karl Rove plans to write books after he leaves the White House 18 months from now.

Them Vs. Them

Via Publisher's Weekly: The NBCC announced today that it is launching a new project tied to its blog, Critical Mass. Critics will take turns blogging about NBCC Award winners and finalists, with the goal of reintroducing readers to the hundreds of authors who have been nominated for or won the literary prize. Some of the pairings include Charles Baxter on William T. Vollmann, David Orr on Elizabeth Bishop, Lev Grossman on Richard Hofstader, and Joshua Ferris on Don DeLillo. The focus of each post will be a discussion of a winning book or nominee. Other posts will feature review roundups, reminiscences of award winners by friends and former students, group discussions, and excerpts from books. The first post appears today.

A Glimpse Into the Advertising of 2037: Expect Thom Yorke Flying Virgin America and Eric Schlosser Eating Big Macs

Today's last news bit is a sad lament care of David Pescovitz over at BoingBoing:

"Two of my patron saints as pitchmen. At left, Timothy Leary's 1993 print ad for The Gap. A copy is currently up for auction on eBay. At right, a still from the William S. Burroughs TV commercial for Nike from 1994. View the blipvert on YouTube."

Tuesday, August 14, 2007

New & Notable: Art Books

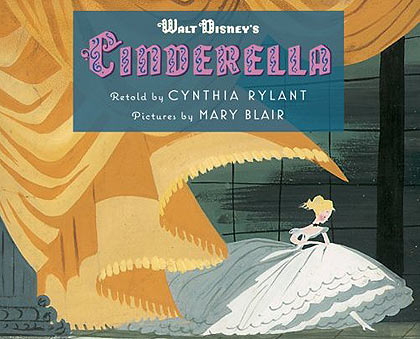

Via Cartoon Brew: A new Cinderella storybook that uses Mary Blair’s concept art from the Disney film will be released August 28th. If you're not yet familiar with Blair's deceptively simple work with pastels and paints (as well as scraps of cellophane and fabric), click here and be wowed. Police guitarist Andy Summers' book of photography, I'll Be Watching You: Inside the Police 1980-83, washes up on our shores August 26th. To view the first 24 pages, click here.

Police guitarist Andy Summers' book of photography, I'll Be Watching You: Inside the Police 1980-83, washes up on our shores August 26th. To view the first 24 pages, click here.

|  |  |  |  |

|---|

Alisa Golden's Expressive Handmade Books would seem to be the sort of fetishistic read that book lovers would salivate over. And unlike the other books mentioned, this one is already out.

Posted by

Inkwell Bookstore

at

12:33 AM

![]()

Labels: book reviews

Monday, August 13, 2007

Pulling Away the Curtain to Reveal the Little Man Behind the Movie Screen

Honest, uncensored accounts of the movie making process are rare. Ones marketed as non-fiction are rarer still. Since Tinseltown's formation some 100 years ago, there have only been a handful of instances where journalists have been allowed unfettered access to every aspect of a film's production (from the creation of the script through the first few weeks following its release; where they were allowed to travel among the cast and crew, taking notes as well as names while documenting the egos, the insecurities, the heartbreaks, the stupidity, the well-meaning disasters and the kaleidoscopic shifting of false blame and unearned claims of credit being made). Among these, two reign supreme: Picture, by Lillian Ross, and The Devil's Candy by Julie Salamon. Reprinted below are reviews of both, written by two of the Hollywood's own -- one a well-known screenwriter and novelist, the other an uncredited scribe for Entertainment Weekly magazine.

November 23, 1952

November 23, 1952

What Makes Hollywood Run?

By Budd Schulberg

Picture

By Lillian Ross.

Miss Ross has anatomized Hollywood," S. N. Behrman has said of "Picture," describing it as "the first blow-by-blow account of what really goes on" and "the funniest tragedy I have ever read."

It is a book with many morals. Perhaps the first and most obvious is that, if you value your privacy, if you do not want to be caught with your clichés down or your pretensions showing, Miss Ross is not the lady to ask into your home. She has explored Hollywood with a camera eye and a microphonic ear. The result is "Picture," which is hardly the "impartial" and "tactful" treatment of Hollywood Miss Ross' publishers claim. (The quality of Miss Ross' impartiality and tact already are well known to The New Yorker's readers of her gentle profile of Ernest Hemingway in 1950.)

I find myself reviewing "Picture" in double vision because in a sense I have already reviewed it: when it appeared in a number (too large a number, it seemed to me then) of New Yorker installments, I reviewed it for my wife and children and friends and anybody else within earshot. Maybe it was what David O. Selnick once described as my "producer's blood" that reacted, but whatever the nature of that fluid it was boiling all the same. I knew it was not good for my soul to fall in with the Hollywood powers, but I found myself echoing their cries of anguish and protest. (In Hollywood a certain trade journalist, with the tolerance for which he is known, closed his column with: "I leave you with two dirty words--Lillian Ross.")

Now that I have read the articles in book form, I find myself wondering whether Hollywood hasn't once more gone off the deep end, an acrobatic feat my home town has perfected through years of practice.

For "Picture" presents Hollywood's more heroic attitudes as well as its more foolish and familiar ones. Never blind to Hollywood's persistent creative effort, it is sharply observant of the business mechanism that blunts the points of some of the industry's sharper talents. It plays back with an unfailing ear some of the wise things that are said in that keyed-up, pent-up industrial town, as well as the wise-cracking, the bathetic and banal.

It was either a lucky or an ingenuous choice that led Miss Ross to "The Red Badge of Courage" as the picture to follow step-by-step from the first ritualistic rumors of High Priestesses Parsons and Hopper to the New York reviews and the box-office returns two years later. The "Red Badge" was the ideal hook on which to hang a study of the classic conflict between serious artistic effort (well, fairly serious and the cold, economic logic of box-office, stockholders and the hierarchy of Loew's, Inc. John Ford knew this conflict when he took a risk with "The Informer" and "The Long Voyage Home," and did his obeisance with "Wee Willie Winkie" and "What Price Glory." For years King Vidor balanced such artistic successes but commercial flops such as "The Crowd" and "Our Daily Bread" with less ambitious box-office winners. Hollywood is not always a Garden of Eden where writers and directors sit by their pools and dream of bigger salaries and bigger pools. A surprising, and largely frustrated, number of them dream of better pictures. For all their insecurity, their compromising, their posturing, these choose--occasionally--to face into the riptide of public opinion and high finance.

John Huston, the director of "Red Badge," and Gottfried Reinhardt, his producer, may remind you of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza in modern dress, this time in Hollywood slacks and English tweeds. They are ludicrous, devoted, ingenious, ennobled, funny when they are being serious and somehow impressive even when Miss Ross catches them (and oh how she loves to catch them!) saying "I always wanted to direct a picture on horseback," or "The titles are just marvelous. . . . Piccolos under your name, strings under mine. You will go out of your mind."

Quotations. Like Durante, Miss Ross has a million of 'em. Only Jimmy is more human. Just the same, Miss Ross makes good her threat to learn something about the American motion picture industry. And her eavesdropping with a vengeance begins to take on the meaning and unity of a novel. Dore Schary, the new tycoon who is for the picture, wins out over L. B. Mayer, the erstwhile or last tycoon who does everything in his power (which is legendary until he is eased out of the studio he founded) to keep the "Red Badge" from being made. "You don't want to make money, you want to be an artist," Mayer accuses Reinhardt. Mayer, like his satellite Arthur Freed, believes in clean, cheerful, romantic, American entertainment. Schary does too, of course, but he's willing to take more chances on off-beat stuff like Huston's and Reinhardt's "Red Badge." Schary stands by the picture in his fashion, trimming it, simplifying it and removing some of the scenes that made teenagers laugh and that Huston and Reinhardt had considered their best.

When it's all over, the picture gets respectful reviews, but not what Huston and Reinhardt had hoped for when they first shared a dream of "a great artistic picture that would also make money." "Red Badge" opens in New York in a small theater to poor business. The Academy Award for that year is won by "An American in Paris," produced by Arthur Freed, the man more interested in making money than making art. And who has the last word? Miss Ross has chosen her Greek Chorus shrewdly. Not John Huston nor Gottfried nor Dore Schary nor even L. B. Mayer sits in final judgment. It is Nick Schenck, who runs M.G.M. from his office in New York as head of Loew's, Inc.

"Now, three thousand miles from Hollywood * * * I began to feel I was getting closer than I ever had before to the heart of the matter," writes Miss Ross. "I felt that somewhere in the offices upstairs I might find the few decisive pieces that are missing."

So finally, upstairs she finds Schenck. And this Caliph of Caliphs says, "I supported Dore. I let him make the picture. I knew that the best way to help him was to let him make a mistake. Now he will know better. A young man has to learn by making mistakes. I don't think he'll want to make a picture like that again."

Nick Schenck is wrong, of course. For all his wisdom, there is a restless, stubborn creative streak in a John Huston, in a Gottfried Reinhardt, even in a Dore Schary brought-to-heel, that will make him say again what Huston says to Lillian Ross as this book opens: "They don't want me to make this picture. And I want to make this picture."

November 15, 1991

November 15, 1991Play Dough

Entertainment Weekly Magazine (writer uncredited...how Hollywood!)

The Devil's Candy: The Bonfire Of The Vanities Goes To Hollywood

By Julie Salamon

Some books arrive with a buzz. The Devil's Candy, Julie Salamon's exquisitely detailed account of the making of the movie The Bonfire of the Vanities, is such a book. Weeks before it landed in stores, le tout Hollywood had already read it and was talking about it. Bernard Weinraub, the New York Times' new entertainment reporter, had plugged it with abandon. Variety, knowing where its bread is buttered, had taken a preemptive swipe at it. In Hollywood, what everyone seems to be asking is: Why did director Brian De Palma allow someone like Salamon-a bona fide journalist from The Wall Street Journal, not some easily controlled hack-to roam free on his movie set? How could he have been so stupid? We non-Hollywood types, however, are likely to have a different reaction-one of gratitude to De Palma, who, as Salamon puts it in her acknowledgments, ''opened the door, without condition, and then never flinched.'' The question of why good people make bad movies has never been answered more persuasively than in this book. It's a question worth asking because, as a general rule, movies have become increasingly banal as they've become more expensive to make. Bonfire cost more than $40 million, and with so much on the line, the instinct is to play it safe. Bad decisions are the inevitable result. Hence, the role of the judge-a Jew in Tom Wolfe's best-selling novel- is given to Morgan Freeman because, according to studio executives, a black actor could offer some ''likability, empathy, racial balance.'' Bruce Willis is cast not because he fits the role of down-and-out journalist Peter Fallow but because he is a movie star and might draw teenagers to the theaters. On and on the list goes. At one point, Warner Bros. president Terry Semel becomes so agitated by the spiraling costs that he demands that De Palma pay any cost overruns for a scene budgeted at $75,000. De Palma promises to bring it in on budget. Semel's is an act of sheer panic, and it makes you realize why Hollywood's creative community is so contemptuous of ''the suits.''

Not that Salamon participates in this contempt. That's part of what makes her book so good; she lends a sympathetic ear as these smart, likable people explain why they did what they did. She also captures something about the context in which movies are made these days. Throughout the filming, controversies erupted, rumors leaked out about trouble on the set, costs soared. All of this backdrop seeped into the public consciousness, so that by the time the movie was released, its notoriety overshadowed the actual images on the screen. Critically and financially, The Bonfire of the Vanities was a bomb, but it's hardly the worst movie ever made, and what stunned the people who made it was not that it failed at the box office but that it was released to such vitriol. They hadn't heard the tom-toms beating in the background. But Salamon heard them, and so did we. That's one of the reasons we stayed away from the movie in droves. In American culture today, movies also arrive with a buzz.

Posted by

Inkwell Bookstore

at

5:21 PM

![]()

Labels: book reviews